|

By Paul Copan

|

Apr 17

|

GenZ, Technology, and Anxiety

We live in an anxious generation—it’s a time of insecurity, self-doubt, and all manner of identity crises—personal, sexual, and spiritual. In the book The Anxious Generation, Jonathan Haidt tells about a young girl who went through an all-too-common GenZ identity crisis:

Alexis Spence was born on Long Island, New York, in 2002. She got her first iPad for Christmas in 2012, when she was 10. Initially she used it for Webkinz—a line of stuffed animals that enables children to play with a virtual version of their animal. But in 2013, while in fifth grade, some kids teased her for playing this childish game and urged her to open an Instagram account. Her parents were very careful about technology use. They maintained a strict prohibition on screens in bedrooms; Alexis and her brother had to use a shared computer in the living room. They checked Alexis’s iPad regularly, to see what apps she had. They said no to Instagram.

Like many young users, however, Alexis found ways to circumvent those rules. She opened an Instagram account herself by stating that she was 13, even though she was 11. She would download the app, use it for a while, and then delete it so her parents wouldn't see it. She learned, from other underage Instagram users, how to hide the app on her home screen under a calculator icon, so she no longer had to delete it. When her parents eventually learned that she had an account and began to monitor it and set restrictions,….

Alexis made secondary accounts where she could post without their knowledge. At first, Alexis was elated by Instagram. In November 2013, she wrote in her journal, “On Instagram I reach 127 followers. Ya! Let's put it this way, if I was happy and excited for 10 followers, then this was just AMAZING!!!!”

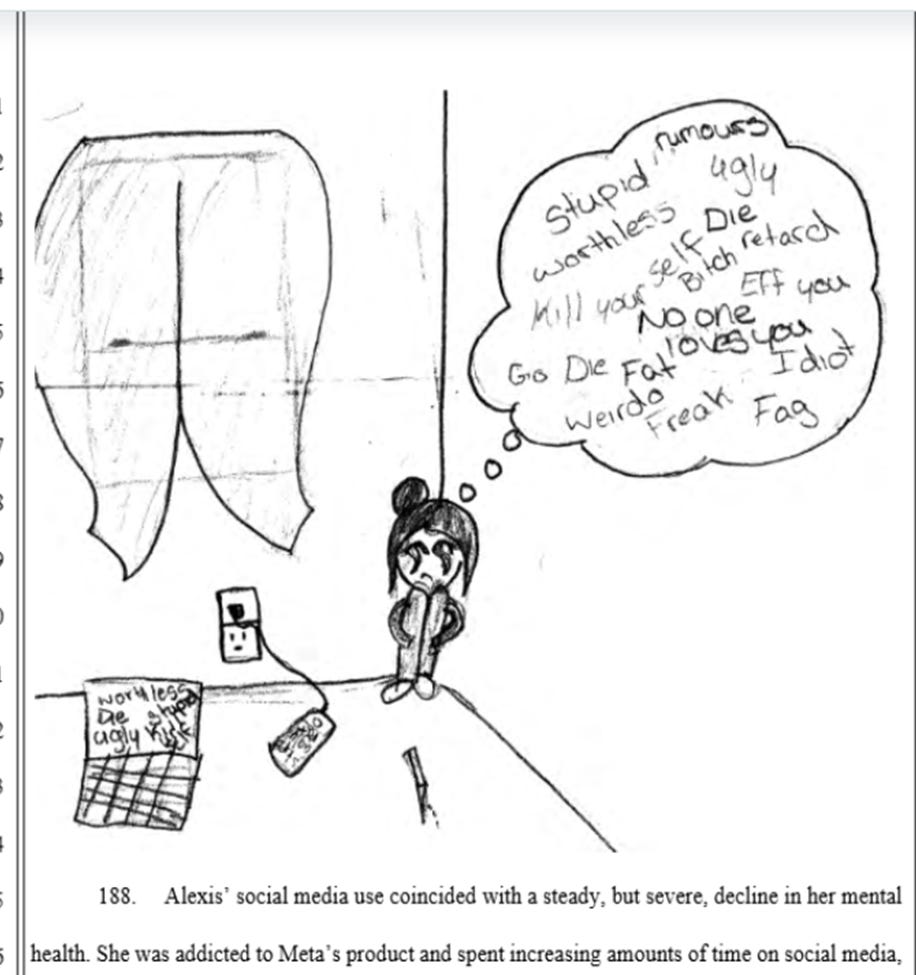

But over the next few months her mental health plunged and she began to show signs of depression. Five months after she opened her first Instagram account, she drew [a] picture [of herself] that expressed self-loathing: “Stupid”; “Die, retard”; “No one loves you.”

|

Within six months of opening her account, the content Instagram’s algorithms chose for Alexis had morphed from her initial interest in fitness to a stream of photos of models to dieting advice and then to pro-anorexia content. In eighth grade, she was hospitalized for anorexia and depression. “She battled eating disorders and depression for the rest of her teen years.”[1]

Best-selling author and professor Jonathan Haidt shows how childhood has now become phone-based; Gen Zers who use iPhones have developed anxiety, depression, self-harm, and suicidal ideation—not just here in the US but also the UK, Canada, the five Nordic nations, and beyond. Harms have come to GenZ—social deprivation, sleep deprivation, attention deprivation, and addiction.

Haidt says humans have had a play-based culture throughout the history of humanity, but something happened between 2010 and 2015: Haidt calls this the “great rewiring of childhood” (smart phone, increased time on social media). Those born after 1995 have become a phone-based culture. This has been a key factor in the rise of mental health issues for young people. Haidt advocates not letting our children have smart phones or access to social media until well into high school (maybe flip phones, if needed). More and more schools are banning cell phone use.

Reducing exposure to social media and screen time for children while encouraging opportunities for play and face-to-face relationships are important strategies for addressing this social contagion. But some who have grown up in the church have been facing a spiritual identity crisis.

Anxiety, the Resurrection, and Christian Foundations

As philosopher Charles Taylor has maintained, we live in a disenchanted “secular age” in which belief in God has become contestable. Ironically, our knowledge of the world hasn’t really changed to justify this megashift. New York Times columnist Ross Douthat asks us to imagine living in the ancient or medieval pre-Darwinian period. During these eras, a good Creator and Designer God explained the core features of reality—human dignity, duties, beauty, goodness, rationality, the meaning of life, human encounters with the transcendent realm. He adds, “Now consider the possibility that in our own allegedly disenchanted era, after Galileo, Copernicus, Darwin, Einstein—all of this is still true.” Despite challenges to faith and the need to process them, “there are also important ways in which the progress of science and the experience of modernity have strengthened the reasons to entertain the idea of God,” Douthat writes.[2]

Those growing up in Christian homes may find themselves doubting the faith of their fathers and mothers. Many are anxious about whether their faith is well-grounded. I get phone calls and emails from parents about their kids in a crisis of faith—and from people in the throes of the faith-crisis themselves. Maybe a lot of us bottle up our questions and doubts about Christianity—and we may find ourselves in the midst of a crisis of faith—another kind of identity crisis.

A good deal of my work involves writing books that attempt to tackle some of the toughest questions in circulation—namely, ones related to the goodness (and severity) of the Old Testament God—Is God a Moral Monster? and Is God a Vindictive Bully? and others.

As we approach Easter, we can revisit the all-important question: Why should I be a Christian rather than a Hindu, a Muslim, an atheist, or a Buddhist? The reason we give is rooted in realism: because the Christian faith is true. We don’t believe that the Christian faith merely “works” or makes us happy or gives us a sense of purpose. Indeed, the Christian story is the story of reality, and by our participating in this story, God transforms our own broken stories and anxious lives to solidify our identity and provide an anchor for our souls.

This story turns on the crucial truth of Jesus’ bodily resurrection—a story that fills Christians with hope because it reminds us that God is with us and for us. This can allay deep anxieties about our identity and fears about our guilty record and the reality of our mortality. This historical fact is a well-founded one. One scholar and long-time friend, Gary Habermas, has devoted fifty years of his life to researching and writing on this topic. This dedication has culminated in the writing of his magnum opus consisting of four volumes of over 1,000 pages each on the resurrection of Jesus, published by B&H Academic. In my coedited Christianity Contested: Replies to Critics’ Toughest Objections, his chapter with Ben Shaw summarizes the evidence, providing us with a “state of the scholarship” report on the historicity of Jesus’ resurrection and showing the growing scholarly consensus about the facts surrounding it.

The landscape has changed since Gary first embarked on this project in the 1970s. The historical value of the New Testament was greatly underappreciated, and skeptics were relying on naturalistic alternatives to explain away the resurrection (“the disciples were hallucinating,” “the women went to the wrong tomb,” etc.). Today, scholars of all stripes who have Ph.D.s in the relevant disciplines generally recognize the rich historical value of the New Testament—even if they don’t believe it’s inspired Scripture. And, as it turns out, critics of the resurrection no longer bother to offer naturalistic hypotheses as alternatives to Jesus’ bodily resurrection; they simply tend to say, “We’re not sure what happened.”

Habermas and Shaw’s chapter reviews the minimal historical facts that point to the resurrection—facts accepted by the large majority of these scholars across the spectrum, from agnostic or atheist to conservative Christian. These facts are available to all historians and are not “supernatural facts,” although a supernaturalistic explanation of those facts makes better sense than the naturalistic explanations and dismissals, which tend to be driven by philosophical bias.

What are these “minimal facts” available to all historians and accepted by the vast majority? Here they are:

1. CRUCIFIXION: Jesus’ death by crucifixion under Pontius Pilate;

2. PRESENTATION: The disciples had experiences of what they believed to be the risen Jesus presented to them;

3. PROCLAMATION: The early proclamation of Jesus as crucified, dead, and resurrected bodily;

4. TRANSFORMATION: The transformed lives of the disciples and of Paul.

To this we can add two conversions that are included in this set of minimal facts:

CONVERSION #1: The conversion of James, Jesus’ skeptical brother;

CONVERSION #2: The conversion of the church’s persecutor, Paul.

We could add other items too. For example, the strongest evidence affirming Jesus’ post-mortem appearances is Paul’s testimony in Galatians, probably written in AD 48-49. There Paul describes his meeting Peter and also James (the brother of Jesus) three years after his conversion (AD 35-36)—and just five years after Jesus’ death. Galatians 1:18-20 uses the Greek term historēsai, indicating Paul’s historical seriousness of purpose in meeting with these disciples. Paul later met with James, Peter, and John, who were direct witnesses to the resurrected Jesus (Galatians 2:1-10). Keep in mind that no scholar disputes that Paul wrote Galatians—or 1 Corinthians, for that matter. And in both of those books, we have rich support for the resurrection of Jesus as a fact of history. As Paul made clear, if it did not take place, there is no Christian faith at all. Paul placed everything on the line: “if Christ has not been raised, our preaching is useless and so is your faith” (1 Corinthians 15:14); if he has not been raised, “you are still in your sins” (1 Corinthians 15:17); “[i]f only for this life we have hope in Christ, we are to be pitied more than all men” (1 Corinthians 15:19).

We could add other evidences—the very early Christian creedal traditions (Romans 1:3-4; 10:9; Acts 2:22-28; 1 Corinthians 15:3-9) as well as the coherence of the various criteria of authenticity used by historians (e.g., multiple attestation, the criterion of embarrassment, enemy attestation). These evidences are rich and worthy of study. For a wonderful summary, see the chapter in Christianity Contested. For an expanded exploration, see Gary’s stunning magnum opus on the resurrection mentioned earlier (and for a preview, see our excerpts from Volume 1 and Volume 2.)

While those growing up in Christian homes may find challenges to their Christian faith in the modern world, their intellectual doubts and anxieties can be addressed by looking at the weight of the historical evidence for Jesus’ resurrection, which sets Jesus apart from any other world religious leader or any others claiming to be authoritative guides. That resurrection is why we should be Christians rather than Hindus, Muslims, or Buddhists. Of course, some may have doubts of another kind. Perhaps it is temperamental doubt (those who seem to be wired to doubt anything, not just “religious” claims), emotional doubt (which stems from a personal or relational insecurity), moral doubt (which arises in the wake of a significant moral deviation), or spiritual doubt (anxiety about the state of one’s standing with God). Each of these species of doubt requires a different approach, and we must, as John Donne wrote, “doubt wisely.” But if one’s doubts about the Christian faith are truly intellectual, the major way to begin tackling this doubt is to examine the evidence for the bodily resurrection of Jesus. After all, so much is at stake. As the noted historical theologian Jaroslav Pelikan wrote, “If Christ is risen, then nothing else matters. And if Christ is not risen, then nothing else matters.”[3]

Notes

[1] Jonathan Haidt, The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness (New York: Penguin, 2024), 143-144.

[2] Ross Douthat, “Guide to Faith,” New York Times, August 14, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/08/14/opinion/sunday/faith-religion.html.

[3] Quoted in Martin E. Marty, “Professor Pelikan,” Christian Century 123 (June 13, 2006): 47.

— Paul Copan is the Pledger Family Chair of Philosophy and Ethics at Palm Beach Atlantic University. Learn more about Paul and his work at paulcopan.com.

image: Holy Women at Christ’s Tomb